The 80s of travels through the bordersbeing careful never to lose the seen necessary to transit, with little more than a map, a camera and some money in your pocket. This is the exciting And visionary I tell that Nicolas de Crécy ago in his Visa Transitgraphic novel published in Italy by Eris Edizioni, now in its second volume. With the simplicity and lightness of the road tripthe author recalls an era that seems to be very far from ours, aboard a grinder which, despite the fact that it always seems to want to abandon its passengers at any moment, crosses a multitude of countries and becomes not only the halfbut also the witness of life that flows between cultures, landscapes, borders that almost no longer exist today. Jump aboard this with us Citroën Visa a little broken and let’s start together to discover this graphic novel.

From France to Turkey

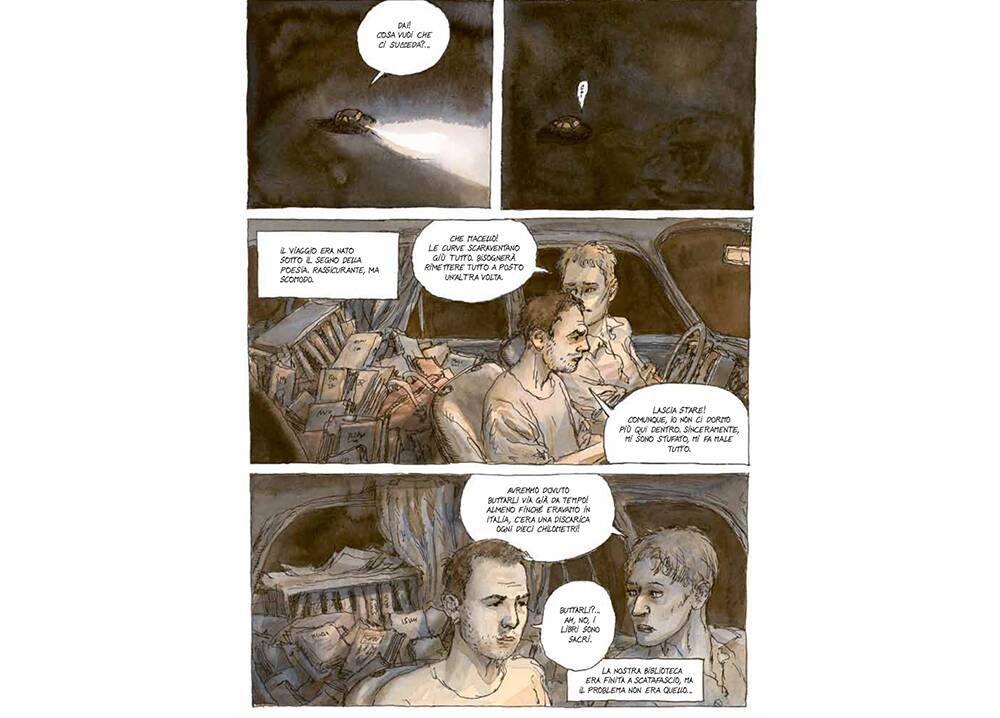

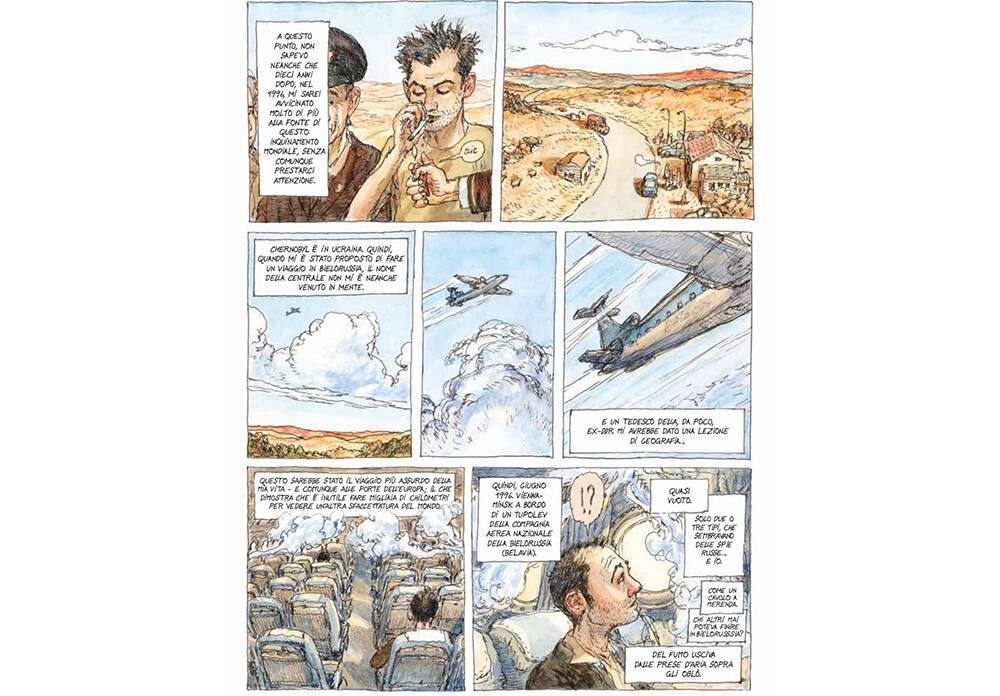

It is the summer of 1986. Nicolas and the cousin Guyjust in their twenties, they set a goal together: to take a road trip to Turkey and back, putting their battered Citroën Visa on the road for the last time, on an adventure that takes them from one country to another transported by the desire for discovery and by a vehicle that could abandon them without warning. The two cousins bring little or nothing with them, but they don’t give up loading even one on the Visa small “mobile” librarycomposed of the best of French literature to which the two young people feel connected.

Once they leave, Nicolas and Guy cross Italythe Yugoslavia and the Bulgariapassing through those areas most affected by the disaster in Chernobylto finally arrive in Turkey. It could have been the Chernobyl tragedy that moved the two young people, marking the ticking of a clock that seems to have put the accelerator on. What better way to spend the summer and youth, then, than by traveling and exploring in this time now fragile and ephemeral? In the company of a Citroën Visa ready for the junkyard, ghosts of deceased poets that occasionally appear when they are misquoted, curious and diverse cultures with new customs for the two protagonists. Along a hot strip of asphalt, without knowing what the next stage will have in store for tomorrow.

Visa Transit: a car, two boys and many borders to cross

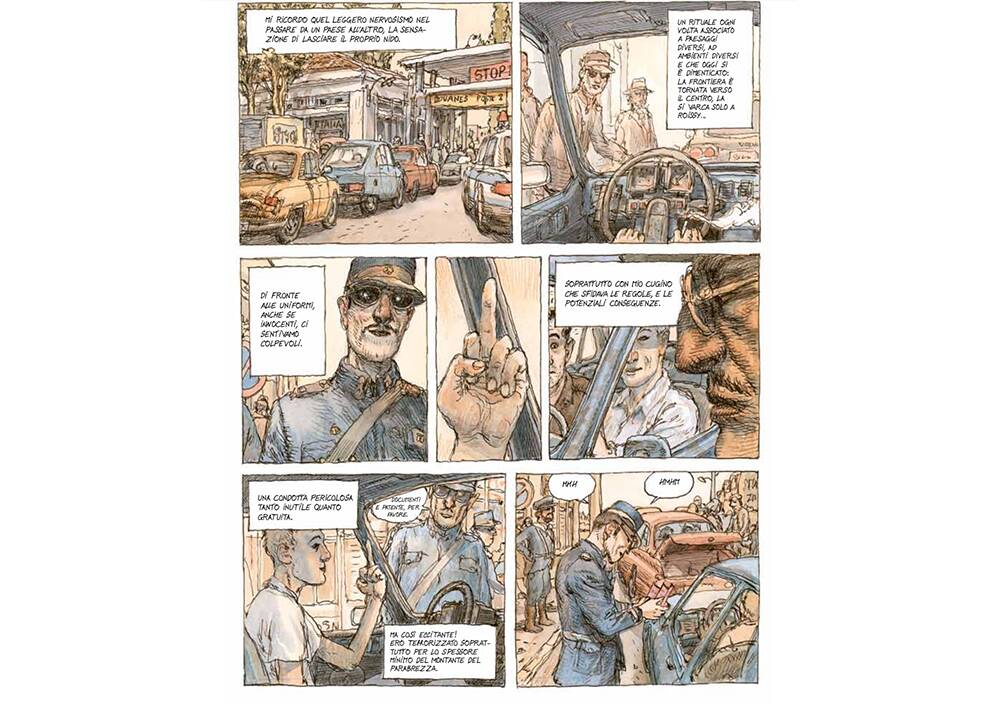

Just drive off with the essentials, a few clothes, some money to make sure you can eat and sleep, a map and a camera. Today for someone all this would be unimaginable. Thinking of embarking on a road trip to Europe without relying on navigator of their smartphone (the writer could not even reach the nearest region without GPS); start with the perspective that from one country to another it may be necessary to show a seen and suffer gods checks; or even just imagine visiting new places without being able to post to Instagram immediately an image of what you are seeing, live. Visa Transit instead it is the story of an era that seems to belong to centuries ago, of a world divided by boundaries and fearswhere everything was different and nothing was taken for granted.

Nicolas de Crécy, French cartoonist former author of Prosopopus, Diary of a Ghost, The Republic of the Catch And The Celestial Bibendumrelies on memories of his youth and through this autobiographical graphic novel, he takes us with him and his cousin Guy aboard a battered Citroën Visa that also serves as a time Machine. The goal is the journey made by the two cousins through what at the time was not yet Europe as we understand it today, in a period in which doubts and post-Chernobyl fears they were always lurking, crossing the borders between countries was a source of anxiety and certainly there were no available technologies on which instead we can count today (to make the Citroën Visa more “futuristic”, a Radar 2000 affixed to the dashboard as a spaceship bridge). The narrative is therefore built on the basis of memories of that trip, with some photos taken during this road trip that come to the aid of the author and, peeking through the pages from time to time, make it more effective real the story told.

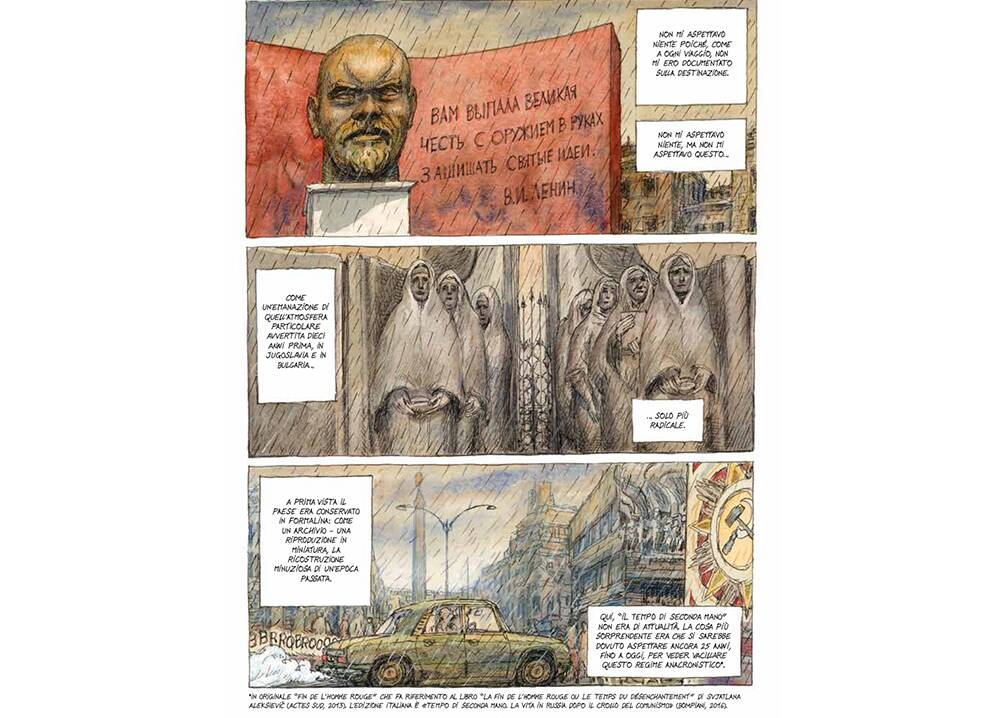

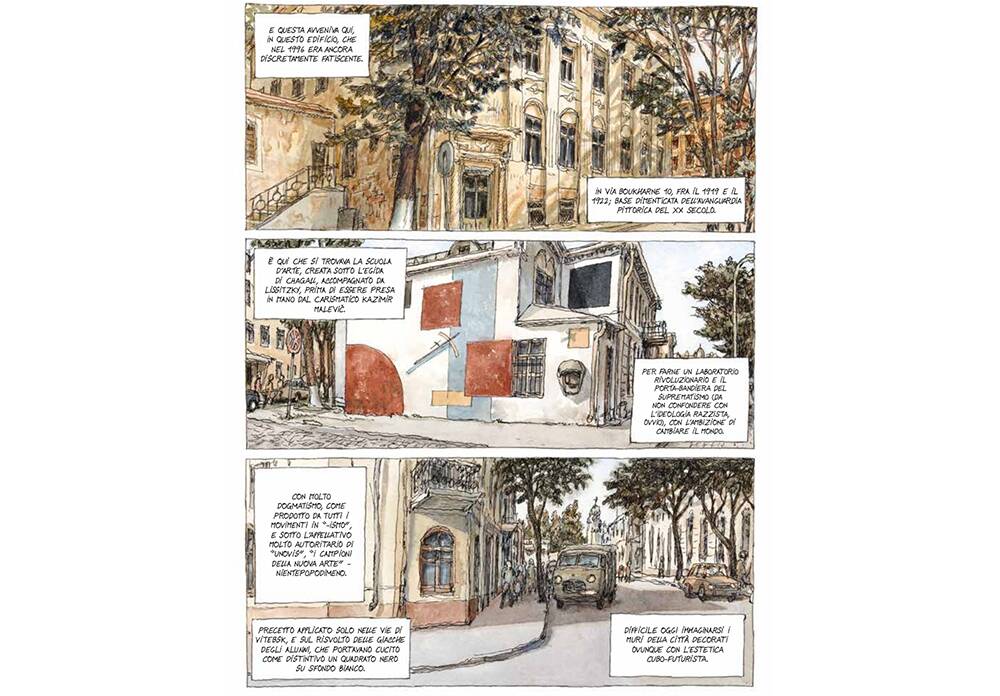

Visa Transit Vol. 2, the evolution of the graphic novel in the second volume

Visa Transit Vol. 2 the road trip of the protagonists continues, letting the flow of the author’s memories have a free flow and reach out towards other memories, connected to this journey. Crossing Eastern Europe, the author Nicolas and the young traveler Nicolas (who merge here breaking down the space-time constraints) recall another journey, the one made years later at a more mature age in Belarus. In 1996, Nicolas de Crécy was invited to participate in an art contest in Minsk and, while the memories of that period resurface, take the opportunity to tell not only the atmosphere of that new place, torn between the brutalism of the high-rise buildings and the artistic sensibility that certain groups have tried to apply to urban architecture. But also the will to live resulting from underground fear of radiationof the poisons nested in the air, in food, in water, spread following the Chernobyl accident a few years earlier.

The youthful journey of the two cousins is then put on temporarily “paused” from this new stream of memories, which, however, does not suddenly and unpleasantly take over from reading, but acts as a a natural connection. A memory in the memory, like those that normally spring in our mind when we think about something from the past and a small detail reminds us of other episodes, other people, other places. In Visa Transit Vol. 2 the journey continues, not as we had expected, but towards another era and another place, still strongly reverberating the same emotions of the past. This digression also allows you to increase curiosity towards the road trip of ’86, which will most likely continue in a third volumealmost giving rise to the need to find out how this journey will end, not only physical, but also mental.

Visa Transit it becomes so a double trip: that of the author, experienced in the first person and described through memories, and that of the reader, lived by proxy but no less adventurous. This graphic novel is indeed an immersive experience in times quite different from today, through burning streets, chaotic cities or welcoming and verdant villages. A road trip the old waya low cost trip under the sign of adventureof the surprises and of discovery, which in an era like the present one, made up of fast flights, comfortable accommodations and reviews on TripAdvisor, opens the door to a totally new world (especially for the new generations who have never experienced similar experiences). Nicolas de Crécy succeeds with his Visa Transit to make us perceive so i inconvenience for example, having to sleep in the car, only to wake up in pain; but also the nostalgia of a touristic and experiential paradigm conceived in a different, more exciting and “reckless” way.

Nostalgia for an era never lived, for those who were not there yet, but also nostalgia for the past for those who lived the 80s in full, when everything was more difficult to obtain and at the same time life seemed more sliding. This is what it feels like to read Visa Transitwhich with a light storytelling and at the same time visionary, tells the flow of memories of an adventurous experience, in which even having to show a visa at the border could be a moment full of excitement and uncertainty. The title of the graphic is not chosen at random: the French term “Visa“In fact translates into Italian as”seen”, And in this case it is also the name of the means of transport that leads the protagonists in “other” places and the reader in a “different” era.

Ironic and visionary

To better understand what Visa Transit manages to transmit, we consider this passage as an example, contained within the first volume:

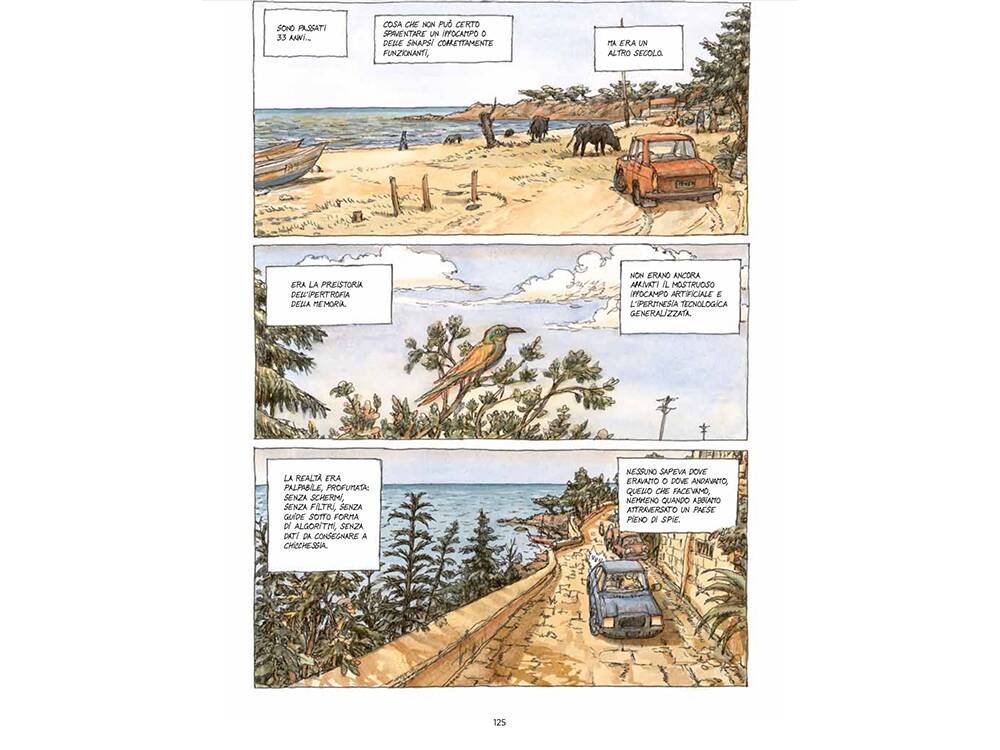

It’s been 33 years… Which certainly can’t scare a hippocampus or properly functioning synapses, but it was another century. It was the prehistory of memory hypertrophy. The monstrous artificial hippocampus and generalized technological hypermnesia had not yet arrived. Reality was palpable, fragrant: without screens, without filters, without guides in the form of algorithms, without data to be delivered to anyone.

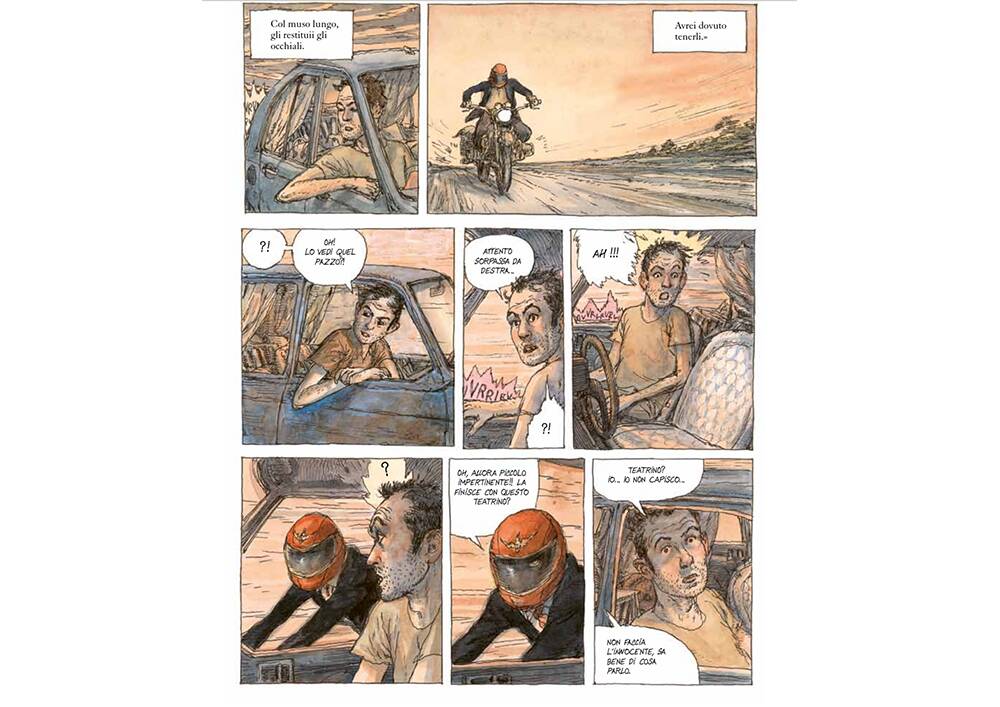

A past world where it was simpler “Touch with hand” what you had in front of you, without the mediation of long sessions behind a camera, or on the screen of a phone in the choice of filters, tags and catchy phrases. But can one be visionary while recounting a bygone era? Nicolas de Crécy certainly is, with his approach ironic and at the same time reflective, in which there is no lack of playfulness And humor behind absurd situations (such as forgetting a backpack containing money and clothes at a gas station, only to realize it 300 kilometers further on). But above all, it is in inserting an element both of disturbance and of “epiphany” for the author-protagonist: the French poet and writer Henri Michauxwho died in 1984, here imagined by de Crécy as a motorcyclist who, in pursuit of the two young men, comes to ask for an account of the quotes that the cartoonist inserts between the balloons.

A narrative that becomes therefore also a halfcasting an eye on concepts of art and artiston the capacity that the different languages have to convey universal concepts with different words and approaches, while paying homage to what for Nicolas de Crécy was certainly a literary point of reference. It is joined by it an original style, the author’s own and unmistakable. While looking for the realismon the other hand his figures appear sometimes grotesque: subtle and detailed inks outline a world that results bizarre, although true. It is a style poeticwhich draws strength from a particular propensity for the fantastic and the absurd principal of this author (one example among all, The Celestial Bibendum). To color these distant memories, the shades of orange, blue, yellowin watercolors and pastels, which make the tables almost sepia-effect images, snapshots of a trip past tinted by the sun and the passage of time. The result is soft and mellow and conveys the perception of a hot and sultry world, but also sparkling as only a summer trip can be.